Panama has been a central focus for the artwork recently displayed in Hege Library.

With Judith Belzer’s colorful paintings of the Panama Canal lining the walls of the art gallery, the saga of Panama-based art continued when a group of students, faculty and staff of Guilford and members of the Greensboro community attended the screening of María Amado and Joe Jowers’ documentary “‘Bien Cuidao:’ The Informal Economics of Survival in Panama” on Oct. 19.

“Bien cuidao,” a shortened version of the Spanish phrase “bien cuidado,” translates to “well taken care of” in English.

This phrase is often heard on the streets of Panama, spoken by car parkers in the downtown area of the city.

Car parkers, peddlers, street vendors and other non-contractual Panamanian workers fall under the umbrella of the informal market.

Informal market workers make up 40 percent of Panama’s work force.

“Informal market employment involves activities of people who are not formally or contractually employed by the government or the private sector, who make a living out of activities in which they get unstable wages and lack Social Security and employment benefits,” said María Amado, co-creator of the film.

Amado was born and raised in Panama City, Panama and is now an associate professor of sociology and anthropology. She teaches courses on racial and class inequality in Latin America.

According to Jowers, “We started out wanting to just give the students in Maria’s class a visual representation of what the informal market was really about.”

Jowers is a filmmaker, photographer and adjunct faculty member at North Carolina A&T State University, where he teaches media analysis.

The informal market is the main focus of the documentary, which is a vivid depiction of the streets of Panama and their occupants. The film is mainly comprised of interviews of members of the informal market and Panamanian experts on this type of economy, conducted entirely in Spanish.

“I don’t speak Spanish, so when we filmed it, it didn’t mean much to me,” said Jowers. “But when this was translated recently to me, I was just like, ‘Wow.’”

Jowers describes his lack of Spanish-speaking ability as both a barrier and a benefit.

“It pushed me to focus more on the visual (aspects),” said Jowers. “So I think it probably is like if you can’t see, your sense of hearing is amplified.”

Amado, on the other hand, is fluent in Spanish and was able to communicate easily with the informal market workers.

“For the most part, in the areas where we were moving the language was Spanish,” said Amado. “We wouldn’t have been able to communicate if I didn’t speak Spanish, and we wouldn’t have been able to create the rapport because of the sense of estrangement.

“I could be more of an insider.”

Amado and Jowers both consider the documentary, which they began working on in 2011, to be a work in progress. They hope to add more footage to the 45-minute film.

The documentary appeared to be a rousing success at its screening.

“I was interested because it’s about how the Panama Canal impacted the indigenous people of Panama,” said Shardae Trout, a junior at Winston-Salem State University.

“It’s super relevant, and it’s interesting to learn how urban development is affecting Panama City,” said sophomore and sustainable food systems major Zach Gruenberg.

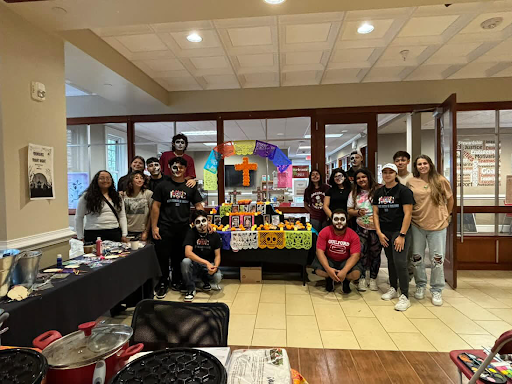

The documentary was displayed in conjunction with a collection of photographs by Amado and Jowers in the first floor hall of Hege Library, entitled “Through a Wide Angle Lens: Visions of Panama and the Canal.”

The photographs focus on economic inequality in Panama by highlighting the difference between the small boats of Panamanian workers and the large ships that pass through the canal.

“The common denominator is the topic of inequality,” said Amado on the relationship between the pictures and the documentary.

The relevance of the photographs is striking due to a $5.2 billion renovation of the Panama Canal finished earlier this year.

“It will allow the biggest ships being built now to cross through Panama,” said Amado. “The economy is growing, but the levels of socioeconomic inequality are also growing.”

The photographs are being displayed through Oct. 30, 2016.

“There’s nothing like seeing Panama, there’s nothing like seeing the kind of poverty that’s there,” said Jowers.

“(We wanted the audience) to see the other side of Panama,” said Amado.