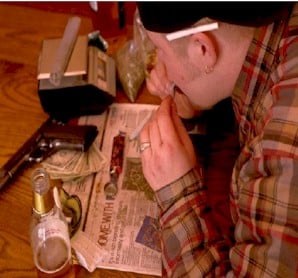

Last November, a new, stricter drug policy was proposed. Students flooded the Senate meeting at which it was discussed, and demonstrated overwhelmingly their disapproval with the proposed policy.Guilford’s current policy, which leaves much to the discretion of the Judicial Board, states that, “on the first conviction, the accused is subject to the following sanctions or a combination” of them, including disciplinary probation, risk assessment, drug education, drug probation, works of restitution, and a loss of campus and housing privileges.

Though the proposed new policy does not differ too greatly, it has two major points of variance: It sets mandatory removal from residential halls as the minimum punishment for even the first offense, and requires immediate notification of the Greensboro Police Department for every offense.

Many students vocalized their disagreement with these strengthened punishments. First-year student Aimee Griffith said, “I don’t feel that the more extreme penalties are necessary. It just creates more fear, which I think is counterproductive to an environment like this. This is our home.”

Professor Max Carter agreed, adding that “the intent of discipline is to help a person lead a whole life. It’s not merely punitive.”

“I don’t think that being firm is incompatible with being nurturing,” said Vance Ricks, a professor of ethics and member of Guilford’s Judicial Board. “The problem lies in finding the balance. . . These types of policies have a high burden of truth on them. You want to say that different circumstances matter, but. . . that route can be a double-edged sword.”

Though many praised the current policy for its examination of individual incidents, it appears that many community members do feel that Guilford needs to clean up its act, as far as drug use goes. Some worry that it will be known as a “drug school,” one in which academics are secondary to the infamous party scene. “When you have your degree hanging on the wall,” commented Senate President Cynthia McKay, “you don’t want someone to walk by and say, `Guilford, huh? That’s a pot school.’ It’s a stigma I don’t want to be associated with.”

The problem, of course, is how to resolve this issue. “In many ways, we’re not equipped,” said Carter. “We’re not the AA. This community is simply not equipped to be a 12-step program . . . We’re always looking for that infallible rule, that infallible way of organizing a community. And it just doesn’t exist. It’s not going to be easy.”

Though stronger enforcement of the current policy was suggested, people repeatedly stated how unnecessary it was to implement a new policy. Perhaps the opinion of senior Tim LaFollette best summarizes the student’s feelings on the matter. “What they’re trying to do by putting up a new policy,” he said, “is like trying to put sprinkles on a moldy doughnut.”

Though the proposed policy, in McKay’s words “worked on a certain level, because it brought the issue to light,” it has been dropped. There remains, however, the problem of the actual drug use and how to end it.