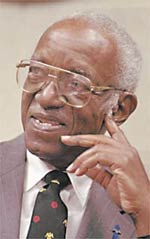

Historian, activist, spokesperson, scholar, inspirer of justice. These are the immediate words to describe John Hope Franklin, a man who has affected the world in countless ways and who spoke in Dana Auditorium Wed., March 6.

The eighty-seven-year-old Franklin, professor of history at Duke and recipient of honorary degrees from more than one hundred colleges and universities, had been courted by the Guilford history department to speak here for the last two years, and last year agreed to read from his upcoming autobiography, The Vintage Years.

“We were surprised he accepted,” said Sarah Malino, chair of the history department. “He’s elderly and incredibly distinguished; it was a very big moment for Guilford.”

Franklin read from his autobiography highlights between infancy and his departure for Harvard graduate school. Beginning with an anecdote of his mother’s denial of a leave of absence to give birth to him, and ending by saying that a $500 loan sent him to Harvard, Franklin illustrated story after story the challenges in his journey through youth.

The centerpiece of the evening was the story of the Dec. ’33 mob castration and lynching in Nashville of a black teenager who had been acquitted of rape because of insubstantial evidence.

“It could happen to any of us,” Franklin said of the realization of students at Fisk University in Nashville, where he was an undergraduate student at the time.

He and fellow student leaders considered a street demonstration, but decided instead to petition President Roosevelt to attend to the issue during the president’s visit to the school in 1934. The students were asked to refrain, and Franklin agreed when Fisk’s president offered him the chance to meet Roosevelt separately in Georgia.

Franklin arrived for the meeting, but the president never showed; he had been lied to, and the meeting was never arranged.

Throughout the speech he repeatedly emphasized the importance of “education as a gateway to change,” both in his own experience and in having a nation that fulfills the potential of democracy.

“I have never worked in an environment more conducive to learning, more beneficial to the development of self confidence,” he said regarding his formative studies at Booker T. Washington School in Tulsa, Oklahoma. He shared the challenge of his most nurturing teacher and principal, Mr. Woods: “Can’t you do better? I believe that you can.”

This no-nonsense, practical but optimistic approach to life probably goes far to explain Franklin’s success in changing the world. He is a person who sees every situation, from race riots in Tulsa, to the lack of extensive black history, to the apartheid in South Africa, and asks, Can’t we do better? His life and body of work are an assurance we can.