t’s 6 p.m. on Monday. You’ve just finished a grueling day of classes, including a math exam and a class discussion on a dense chapter in your textbook. To top things off, you got to class late and missed an appointment with your advisor.

For some students, a day this stressful is rare. For many students with dyslexia, this scenario is common.

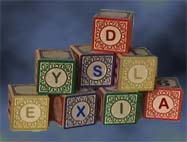

Dyslexia is an anomaly of development that affects 10-15 percent of the U.S. population. It is usually hereditary and causes learning difficulties in spelling, reading, writing, and short-term memory. Many people are diagnosed with dyslexia during childhood, when they put syllables or words in the wrong order (for example, “dap tance” instead of “tap dance”).

Children with dyslexia may learn to read later than usual, and their struggles with reading are most difficult in college. Dyslexics tend to take longer on assignments and exams, which takes time from extracurricular activities and “chill time” – a catch-22, since they often need more study breaks to stay focused.

Dyslexia also has long-term effects outside of the classroom.

In addition to the many things expressed in writing (newspapers, street signs, bus schedules), people with dyslexia often become disoriented and have trouble following instructions in order, identifying left from right, and organizing their time.

These difficulties, along with the low grades and test scores that often result, may cause the person with dyslexia to have low self-esteem.

Sue Keith, Director of the Academic Skills Center, has seen this first-hand. “As with all learning differences, dyslexia can be seen as indicating a lack of intelligence – which is, of course, not at all true. To say that one is ‘dyslexic’ is really just the beginning of a conversation that needs to be heard and honored.”

Many students with dyslexia find it so hard to keep up and do well in school that they drop out. They often take an extra year to finish school, and while this is not uncommon in college, it is much more demoralizing in elementary or high school.

Lesley Varnadore, a senior CCE student who is dyslexic, has experienced this first-hand. “In grade school in the 1960s no one knew why I could not read and spell, so I didn’t like school. Most teachers just thought of me as one of the children that would not make it in the world of school.”

As Varnadore saw, many people who have dyslexia are discouraged from applying to college. “The first time I was diagnosed was in 1987 and the lady that did the diagnosis testing told me that I would not be able to go to college.”

There are resources to aid with the difficulty dyslexia brings.

RFB&D (Recording for the Blind and Dyslexic) is an organization that provides taped books, free of charge, to those who have dyslexia. Kurzweil Reader, a computer program that involves a computerized voice reading text material, helps dyslexic students to read more quickly and understand more.

“Enabled by technology – whether through RFB&D or Kurzweil Reader,a student can read more quickly and accurately, with less fatigue, thus evening the playing field, so to speak,” Keith said. “With Kurzweil, they can take notes, etc., so the whole experience is more like reading and studying a book in what most of us consider the ‘normal,’ unaided way. Both technologies allow a student to use two modalities, too – visual and aural. That’s always a good thing.”

The Academic Skills Center emphasizes the fact that all students learn in different ways, and it helps students to find ways that most help them.

Varnadore believes that people with learning difficulties should learn how to cope with them.

“Many people talk about overcoming their L.D.,” she said. “I think that you don’t overcome L.D.s. I think you just have to work harder and longer and for more time. This L.D. will be with us always.

Categories:

Focus on Dyslexia:

Rebecca Muller

•

February 20, 2004

(Kevin Bryan)

0

More to Discover