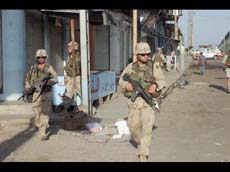

The Iraqi city of Falluja is besieged. Smoke surrounds toppled mosque minarets. Civilians trapped in the battered city describe horrific accounts of death and destruction. “There are more and more dead bodies in the streets,” an Iraqi journalist in Falluja told the BBC. “The stench is unbearable.” Falluja has been an insurgent command-and-control center, as well as the base for the network of Jordanian militant Abu Musab al-Zarqawi. As of Nov. 15, U.S. forces had taken control of 70 percent of the city, including the mayor’s office in central Falluja, according to the BBC. Lt. Gen. John Sattler of the U.S. Marines said that most members of the insurgency “are now in small pockets, blind, moving across the city.”

The campaign for Falluja, Operation New Dawn, began Nov. 8 with 10,000 U.S. and 2,000 Iraqi soldiers. So far, 1,200 insurgents and 38 U.S. and six Iraqi soldiers have lost their lives. Ayad Allawi, the interim Iraqi prime minister, said he believes no Iraqi civilians have been killed. However, Mohammed Farhan Awad, an Iraqi relief committee member, said he saw 22 bodies buried beneath rubble in the northern Jolan district of Falluja Nov. 14, The New York Times reported.

Nicole Choueiry, a spokeswoman for Amnesty International, said she also believes there have been civilian casualties.

“According to what we’re hearing and some testimony from residents who have fled Falluja, it looks like the toll of civilian casualties is high,” she told the Associated Press.

The U.S.-led offensive in Falluja met resistance from insurgents who engaged mainly in guerrilla warfare. Fearing that those insurgents would abandon their weapons and mingle with refugees in order to avoid capture, U.S. troops have stopped many Falluja residents from fleeing the city. Only men aged younger than 15 or older than 55 and women and children have been allowed to leave, according to the A.P.

“There is nothing that distinguishes an insurgent from a civilian,” an anonymous 1st Calvary Division officer said. “If they’re not carrying a weapon, you can’t tell who’s who.”

The BBC reported that as many as 50,000 of Falluja’s civilian population of 300,000 have been unwillingly caught in the middle of urban warfare.

Heavy security has also undermined relief efforts.

International aid organizations have been unable to reach civilians inside the city, according to the A.P. Ahmed Rawi, the Baghdad spokesman for the International Committee of the Red Cross, said that a convoy carrying aid made it to Falluja General Hospital, which is on the outskirts of the city, Nov. 15, but that it could not enter the conflict zone.

“I can’t sacrifice the lives of the volunteers; it is very dangerous to go inside Falluja now,” Ismail al-Haqi, the director of the Iraqi Red Crescent Society, said.

CNN.com reported that violence spread from Falluja to the cities of Baghdad, Baquba, and Mosul Nov. 12.

In Baghdad, insurgents shot down a UH-60 Black Hawk helicopter, injuring three of the four troops on board. Northeast of Baghdad, in Baquba, insurgents clashed with Iraqi police forces. Two Iraqi police officers and two Iraqi civilians were wounded. In Mosul, U.S. and Iraqi forces withstood hit-and-run attacks.

George Guo, a professor of political science at the college, said that the United States is feeling challenged to establish order in time for the elections scheduled to take place in January.

Mohammed Algilany, an Iraqi-American senior at UNCG, says he does not put much stock in those elections.

“I don’t really know if it’ll help,” he said. “They banned a lot of groups from participating. A lot of those groups really do represent the people. It’s the government trying to silence any sign of opposition. They don’t have any connection to the people in Iraq. Most of them were expatriates for the last 25 years.”

Algilany suggested that the United States leave, and give the Iraqi people more control over the government.

“With the exception of the Kurds, and a fairly large population of the Shiites in the south, Iraqis are against (the interim Iraqi) government,” Algilany said. “They view this as an occupation. They view (the U.S. and Iraqi governments) as one and the same.”

Algilany is also unhappy with Allawi, who, after being forced into exile by Saddam Hussein, lived outside Iraq for over 30 years.

“My mother went to medical school with him,” he said. “Allawi was a terrible student. His wife would take notes for him.”

CCE junior Fenita Short said she also believes the United States should step back. “Nobody wins in war,” she said. “I think the troops should come home.”

Guo disagrees. “That’s not a good idea either,” he said. “That’s not responsibility.”

Robert Duncan, another professor of political science at the college, concurred. “You can’t undo what’s been done,” he said. “The least you can do is make things right before you leave.”

However, Duncan said he senses that the conflict in Iraq is a no-win situation. He foresees a power struggle between rival factions if the United States pulls out of the country, but believes that the continued U.S. presence is a lightning rod for anti-American sentiment.

“I don’t know what the answer is on that,” he sighed, with tears in his eyes. “I empathize, and my heart breaks. (Iraqi civilians) are put in a kind of situation that makes me angry. I can only feel their hurt and their pain.”

Twenty months after President George W. Bush declared an end to major combat operations in Iraq, violence still rocks the country.

“I am getting used to the bombardment,” a Falluja resident told the BBC. “I have learned to sleep through the noise – the smaller bombs no longer bother me.”