In 1968, Martin Luther King Jr., gave his “I Have a Dream” speech. His dream included equality for all people. Another man stood up in King’s honor on Wednesday, Jan. 19 in Dana Auditorium and reiterated King’s words on racial equality.

He also called all races, religions, and creeds to stand up and fight for a common cause: saving our planet.

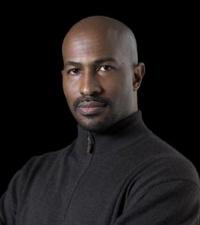

“Many of you are here because you’re strange,” said Van Jones in his speech. “You’re here to hear a black guy talk about green stuff. You’re strange, but you’re also big-hearted.”

People from in and around the Guilford community came to hear Jones’s speech, entitled “Remember the Struggle, Live the Dream.” Jones represents a philosophy that connects sustainability, a green economy, and social justice.

“So many departments came together and pulled funds to have Jones come here,” said Kim Yarbray, the project and communication manager for the Center for Principled Problem Solving. “This (event) shows Martin Luther King, Jr. is for everybody.”

The Africana Community, the multicultural education office, the Bonner Center, CPPS, the Office for Student Leadership and Engagement, LGBQTA Community and the Lilly Foundation combined forces to help sponsor Guilford’s Martin Luther King, Jr. Day celebration.

Jones’ accomplishments are extensive enough to cover two to three people’s resumes. He wrote the best-selling book “The Green-Collar Economy”. He also co-founded such organizations as Green for All, the Ella Baker Center for Human Rights, and Color of Change.

“We don’t have many black male mentors or advisors on this campus,” said junior Adam Watkins. “Jones is a great example.”

Jones worked with the Obama Administration in 2009 as green jobs advisor. He holds a joint appointment at Princeton University in the Center for African American Studies and certain programs at the Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs. TIME Magazine named Jones one of its 100 Most Influential People in 2009.

“There are no signs saying: ‘Apply here to change the world,'” said Yarbray. “It is a constant process of discernment. Van Jones carved out his own path.”

Jones’ journey began in Oakland, Calif., as a lawyer. He demanded social justice and equal treatment within the criminal justice system for people of color on non-violent drug charges.

Jones said that this type of crime spanned all races, but he saw that whites were given a second chance and sent to rehab while people of color were sent straight to jail. Jones said that during this time in his life he thought that he would “let the white people deal with the planet” while he dealt with the people.

Jones found that being a lawyer wore him down, and as a result he soon began a new stage of his life.

Jones said that he started to learn about yoga, spiritual retreats, and tofu. He began comparing the urban communities of Oakland with the richer neighboring communities such as Marin County, Calif.

These richer communities had less pollution, solar panels, hybrid cars, and organic food. Jones saw the benefits of these communities and their lifestyle.

“I started to feel better,” said Jones. “I wondered why I had to drive all the way over here (Marin County) for something as simple as healthy food and clean air.”

If one walks into a health food store and then into a fast food restaurant they will see a drastic difference in price. To Jones, this does not make sense.

“We shouldn’t have to go down to Whole Foods to get our food,” said Jones. “It seems like a whole paycheck, and you come out with one strawberry. I’m healthy but I’m hungry.”

Jones stressed that the environmental movement needs to include all people. King lived in a time where pollution was not a key concern, but Jones carried into his speech a message reminiscent of King and layered it with his vision of saving the planet and therefore our future.

“I cannot imagine a future that’s green, that’s unjust,” said Jones.

He briefly shared ideas for all communities such as growing their own food. His book, “The Green-Collar Economy”, goes more in depth on these points and he has co-created organizations that have pioneered the green economy model.

Jones expressed that people of color are the primary folks that bear the brunt of the environmental turmoil. The topic of the Greensboro White Street landfill was raised briefly in Jones’ speech.

“All of us create trash but only some of us have to live in it,” said Jones. “We get hurt first but benefit last when it comes to getting the hybrid cars or the organic food. This is eco-apartheid.”

Jones mentioned two different groups of people and their issues with the green lifestyle. He said that some African Americans feel this is strictly a white issue.

Jones wanted people of color to remember their ancestors who respected the Earth. He shared the history of when colonizers came to certain regions and put a price tag on pieces of land and soon a price tag on human beings as slaves.

He asked people of color two key questions: “How colonized are you and do you know nothing of your history?”

Jones then shifted to confront those issues already deeply rooted in the green movement. Jones said that many environmental activists seem to focus so much on the importance of recycling inanimate objects that they fail to fight for their fellow human beings.

“If a child can be thrown away in a prison and can’t be given a second chance, but an aluminum can is given a second chance, that’s an inconsistent moral condition,” Jones said.

Terence Muhammad, a community activist, came to the speech and shared a key point he learned from Jones.

“It’s our responsibility to see everything and everybody as part of the environmental cause,” said Muhammad. “This includes animals, trash and people.”