Europe might seem like a great vacation destination, but it has not been able to escape the financial crisis that is affecting the entire world.

The International Monetary Fund, an organization that helps oversee and stabilize the global financial system, said in their semiannual meeting last week that they can meet its current obligations to provide aid to countries in economic distress, but this could change if the crisis worsens.

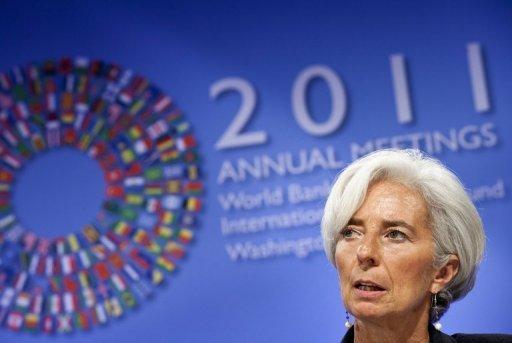

IMF chief Christine Lagarde said that the eurozone must increase the powers of its bailout fund and ensure that investors who hold debt from the troubled economies are not unduly hurt, reported CBS News.

“Failure to undertake decisive action could rapidly spread tensions to the core of the euro area and result in large global spillovers,” said the IMF in their latest economic report. “Contagion to the core euro area, and then onward to emerging Europe, remains a tangible downside risk.”

The European Financial Stability Facility was set up in 2010 to combat the debt crisis in Europe. The BBC reports that legislators feel they need to concentrate on recapitalizing banks and boosting the funds of the EFSF.

Europe’s finance ministers agreed to raise their guarantees for bailout loans given out from the current rescue fund to €780 billion ($1.1 trillion) from €440 billion. That will allow the fund to lend out a total of €440 billion, up from about €250 billion currently, reported the Wall Street Journal. The plan could also allow the European Central Bank to buy more Italian and Spanish bonds to prevent them from needing a full bailout.

“It is very important that we see a combination of the ECB and the EFSF,” said Antonio Borges, the head of the IMF European department, who is urging the ECB to play a bigger role in fighting the crisis. “The ECB is the only agent that can really scare the markets.”

The ECB has bought sovereign debt from Greece, Portugal, Ireland, Italy, and Spain. It has also lent money to banks whose main asset is that same debt. Lending from the ECB is making sure that banks from those countries have enough funds to operate, while worried depositors are withdrawing funds.

“Bank regulation is making the situation worse: banks carry most of the ECB and sovereign debt at face value,” said John Cochrane, a finance professor at the University of Chicago, to the Wall Street Journal. “Their own governments are pressuring banks to buy more sovereign debt.”

Now that the EFSF has the funds to help the countries that are struggling financially, Europe’s focus is now on Greece and whether or not it will need to restructure its debt. A Reuter’s poll of economists showed a majority believe Greece will restructure its debt. Most fund managers only expect Athens to pay back half of what it owes.

According to Reuters, the IMF is ready to provide more aid to the country that sparked the debt crisis in 2009, but Greece still had plenty of untapped potential to raise extra cash itself though privatizations.

“The Greeks have to take the initiative, and so far they have not approached us,” said Borges. “The IMF stands ready (to provide additional support) as a matter of policy.”

While the markets are increasingly concerned that Greece will never be able to repay its €327 billion debt and will have to restructure — creating massive losses for investors that will in turn create severe consequences in the euro zone and beyond — the country still depends on €52.5 billion of IMF aid, reports the BBC.

“Leveraging the €440 billion bailout fund by borrowing from the ECB, and using the fund to insure debt rather than to buy it, in this way the fund could support trillions of euros of debt,” said Cochrane. “But risk can only be transferred; it does not evaporate. And the risk ends up at the ECB and, ultimately, with taxpayers.”