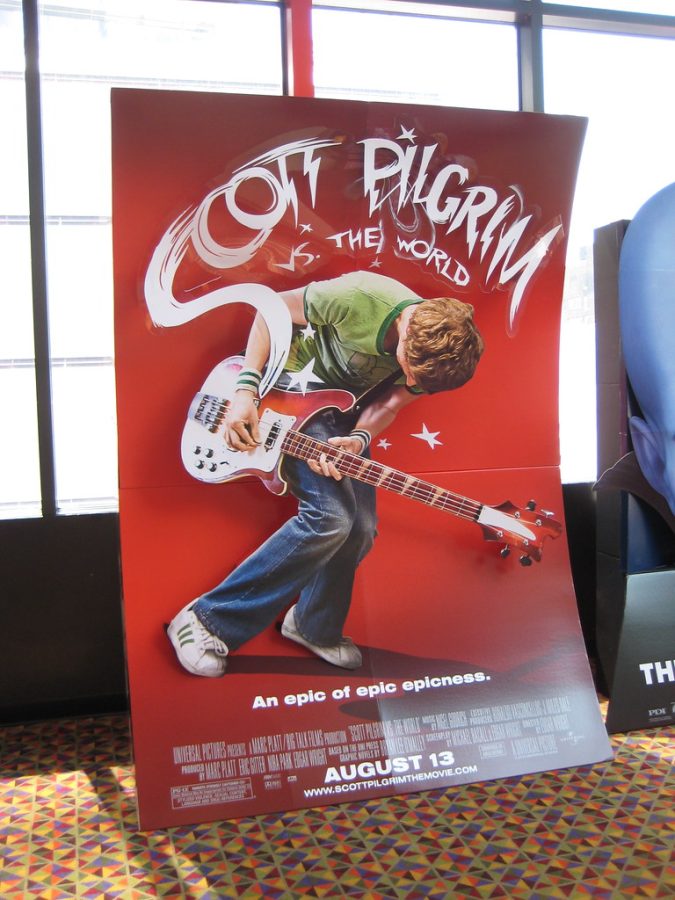

‘Scott Pilgrim vs. The World’ is a cinematic masterpiece

Starring the master of one role, Michael Cera, “Scott Pilgrim vs. The World” may be the worst movie you’ve ever seen. But that’s what makes it such an incredible work.

Based on the comic book series by Bryan Lee O’Malley and directed by Edgar Wright, the 2010 movie has an 82% rating on Rotten Tomatoes but bombed at the box office.

Although other movies starring Cera in the same time period, including “Juno” and “Superbad” (also with Jonah Hill), did extremely well, “Scott Pilgrim” seemed to fall short of the teenage/young adult audience it was meant for. Cera essentially plays the same role in almost every movie: the awkward, almost realistic teenage dirtbag.

Scott Pilgrim (played by Cera) is the bassist of a small garage band and an awful person. He’s a 23-year-old dating a 17-year-old high schooler named Knives, although the most they ever do is hold hands.

Knives Chau (Ellen Wong), his 17-year-old girlfriend, is a Chinese-Canadian girl attending a private Catholic high school. Her name and innocent nature reflect the subtle racism toward, and fetishization of, Asians in western media that is still prevalent today, although it’s slightly less direct.

In the film, Scott meets a girl named Ramona Flowers, (Mary Elizabeth Winstead) while he is still dating Knives. In order to date Ramona, he must defeat her seven evil exes. What makes this movie so great is that it’s not automatically clear what exactly is going on.

Scott’s band, “Sex Bob-Omb,” competes in a Battle of the Bands-esque competition to win the prize of a record deal with the illustrious Gideon Graves, who happens to be one of Ramona’s exes.

Ramona enters the movie by roller skating into Scott’s dream, which is downright iconic, in my opinion.

I think that this lack of seriousness is why this movie gets so much undeserved disrespect. It is whimsical and looks surface-level (which it somewhat is), but when you dig a little deeper, the film shows how Ramona was in the wrong in many of the situations she got into.

For example, she uses both her first ex, Matthew Patel, and fourth ex, Roxy Richter, to get away from the stereotypical men in her life.

“It was football season, and for some reason, all the little jocks wanted me,” she says in the film when explaining why she decided to date Matthew. “Matthew was the only non-white, non-jock boy in school, probably in the entire state, so we joined forces and took ’em all out.”

Ramona calls her relationship with Roxy, who is dubbed “Sapphic Aggressive,” part of a phase.

“I was just a little bi-curious,” she tells Pilgrim.

In both instances, she uses other people to experiment without really taking their feelings into account.

Many of Ramona’s exes are people that she used to get back at someone else. For example, she used Matthew against the so-called “little jocks.” However, she moves to Toronto in order to become a better person and to reinvent herself. Her moving is supposed to represent a shift in her mindset, as, later in the movie, she makes it clear that she wants to be in a genuine relationship with someone, not to fall back into her previous ways.

This nuance in the characters of both Scott and Ramona, along with the shocking graphics and special effects, creates an entertaining cinematic experience and leaves room for deeper analysis. The exes all have these almost-supernatural powers, which Scott combats in video game-esque battles.

Scott’s major character flaw (other than dating someone six years younger…and a minor) is victimizing himself – he is painted as having been wronged by his ex, the lead singer of the band “Clash at Demonhead.”

Envy Adams, played by Brie Larson, seems to constantly get in Pilgrim’s way. She asks Scott’s band to open for her band’s private show, insinuating her obsession with him and making him miserable. But although she is portrayed to be more than a little crazy, he never really seems to be over her.

You begin to see how the movie seems to be made from Scott’s perspective of the world the longer you watch. For example, Ramona doesn’t once appear on her own in the entire movie, taking on the “manic pixie dream girl” trope of the early 2000s.

Even without any hidden meanings, the movie is fun to watch and utterly ridiculous. It’s an ode to terrible rock bands and being a young adult. It was ahead of its time, and if it had a little more time, or if society knew amazing cinema when they saw it, it would be a beloved classic.

Scott rooms (and shares a bed platonically) with his gay roommate. One of Ramona’s exes is a girl named Roxanne “Roxie” Richard, who provides an almost surprising amount of queer representation. In the fashion of the “manic pixie dream girl” trope, she changes her hair color every week, and most of her exes are moody, weird men. Chris Evans plays one of her exes, a superhero actor… with the Captain America theme song and all.

Of course, the movie is flawed. Matthew Patel fights to stereotypical Bollywood music, and Ramona’s last ex calls Knives “Kung Pao Chicken.” Ramona lacks actual depth, and the movie shows the influence of white hipsters and Micheal Cera-esque awkwardness.

Nevertheless, the film takes so many aspects of growing up into account, and although it’s a Canadian film, the experience of being a young adult hasn’t conceptually changed all that much in 10 years or across borders.