A young girl’s screams pierce through the silent night. Unseen forces writhe within her, defying physics and causing her to surrender her own morality. It is demonic possession unlike anything seen before, and it all claims to be based on a true story. This is only halfway true.

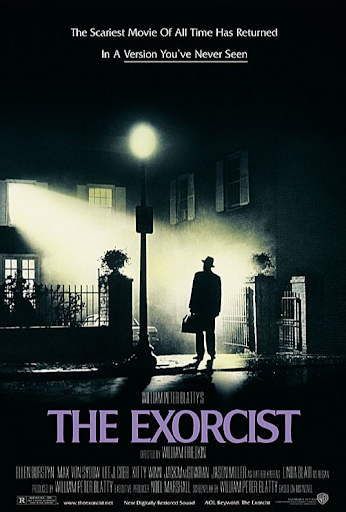

William Friedkin’s “The Exorcist,” the 1973 horror classic deemed the scariest film in history, recently has been revitalized with the release of a sequel “The Exorcist: Believer” on Oct. 6.

The public’s view into the enigmatic religious rite of exorcisms has been oversimplified and sensationalized since the 1970s, but thanks to the new addition to the franchise, some gaps in its portrayal have been accounted for.

The quote “Life imitates art far more than art imitates life,” from 19th century writer Oscar Wilde, explains a lot about why the story portrayed in “The Exorcist” has been an accepted depiction of exorcisms for decades. Humans have an inclination to receive stories as fact and assimilate them into their understandings of life, especially when the infamous “based on a true story” tagline flashes on the screen. However, one of the goals of film is to exaggerate the truth for the sake of entertainment.

The depictions of exorcisms in films like “The Exorcist,” “The Pope’s Exorcist” and “The Conjuring” have been heavily criticized by Catholics for their exaggeration of the abnormality of the ritual, their illustration of the devil’s power being equal to that of God and even their slandering of the Vatican.

One of the main protagonists in “The Exorcist” is the priest Damien Karras, played by Jason Miller, who sacrifices himself to save the life of young, possessed Regan MacNeil, played by Linda Blair. Although it is true that ordained priests are tasked to lead exorcisms, Father Francesco Bamonte, president of the International Association of Exorcists, critiques these films in Catholic Herald magazine. Bamonte states that films underplay or fail to mention “the marvelous, stupendous presence and work of God” and Mother Mary in the ritual.

In an article by The Guardian, Bamonte and the Association of Exorcists also call out the hyperbolic depiction of demons’ violent reactions to exorcisms, saying that the battle between good and evil in real exorcisms is not as close as it is in films.

“Satan is not the god of evil against the God of the good, rather he is a being who God created … Satan and the spirits at his service, therefore, are not omnipotent beings, they cannot perform miracles, they are not omnipresent,” Bamonte said.

One of the newest horror films tackling a “true story” about exorcisms is the 2023 Russell Crowe film, “The Pope’s Exorcist,” which follows Crowe’s portrayal of Father Gabriele Amorth, the chief exorcist of the Vatican, in his discovery of secrets concealed by the Vatican. The IAE released a statement in response to the film’s trailer that says the movie had “a ‘Da Vinci Code’ effect … insinuat[ing] the usual doubt in the public: who is the real enemy? The devil or ecclesiastical ‘power’?”

Although aspects of Catholicism are sensationalized in movies, for the most part, the actual process of an exorcism is accurately portrayed, from how to decide if an exorcism is needed to the steps of incantation and the use of holy water.

These films are also very Catholic-oriented, despite other world religions like Islam, Judaism, Hinduism and Haitian voodoo having their own variations of removing evil spirits or temptations from the inflicted, with processes that are similar to an exorcism in the Catholic sense.

“The Exorcist: Believer” addresses the fact that similar rituals are seen in cultures around the world, as the exorcism of two young girls is done by a sundry coalition of people from the Catholic, Pentecostal and Baptist denominations, and even an expert in the African-American practice of rootwork. The film also features symbols of Haitian voodoo and African spirituality.

By incorporating a variety of religions, “Believer” communicates that the fight against evil is accomplished by a union built around the strength of faith and belief, which, as the title suggests, transcends the boundaries of religious differences.

In his book, “An Exorcist Tells His Story,” Father Amorth wrote, “It is thanks to movies that we find a renewed interest in exorcisms.” So, while it is true that any publicity is good publicity in this sense, many people see “Believer” as a better step towards religious inclusivity and respect in the film industry.