Stevenson speaks at Bryan Series

Lawyer teaches community about humanity

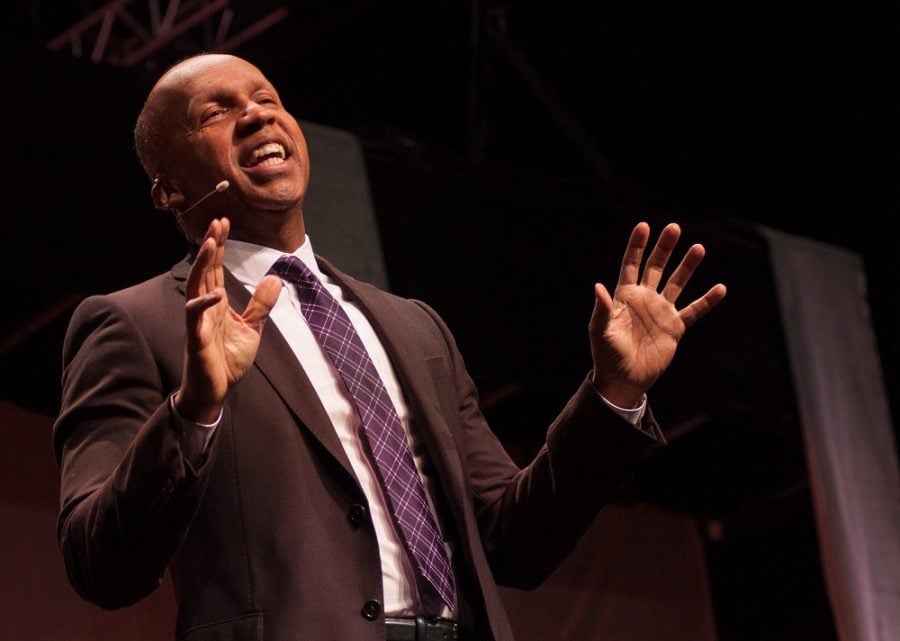

Photo by Francesca Benedetto/Guilfordian

Bryan Stevenson, founder and Executive Director of the Equal Justice Initiative, speaks at the Greensboro Coliseum Complex on February 21, 2017 in Greensboro, North Carolina. Stevenson discusses his work with incarcerated children, death row inmates, overturning wrongful convictions, and fighting racial injustice in the criminial justice system.

Bryan Stevenson had never met a lawyer when he started law school.

This turned out to be an advantage.

Because he was unaware of the corporate culture in law school, Stevenson explained in his Bryan Series lecture, he was able to find his own path — one that lead him to fight for the wrongfully incarcerated, prisoners on death row and juvenile offender.

“(Stevenson shows us) people in their humanity and in our humanity,” said Barbara Lawrence, associate professor of justice and policy studies and associate academic dean, on the College’s Higher Education in Prison program. “(He shows us) we have to care, … and we have to do the work.”

Stevenson is the founder of the Equal Justice Initiative, an national organization based in Alabama and dedicated to representing death row inmates and creating a more equitable criminal justice system.

His speech on Feb. 21 was the culmination of a number of events at Guilford College around the issue of criminal justice reform. These included an on campus book club on Stevenson’s “Just Mercy” and a presentation on Feb. 19 by Lawrence about the College’s Higher Education in Prison program.

Stevenson also did an extended Q&A on campus, answering questions on everything from career advice to treating trauma within communities.

“His approach to the death penalty … involves a refreshing breath of empathy,” said sophomore Austin Bryla. “I think his approach (is) something we can all learn from.”

During his speech in the Greensboro Coliseum, Stevenson explained how he had discovered this empathetic approach to the law. During an internship as a law student, he was sent to tell an inmate he would not have an execution date in the next year. It was the first time he had ever met a condemned person.

“It turned out we were exactly the same age,” said Stevenson. “We had the same birthday: same day, same month, same year.

The two men started talking.

“Forty-five minutes turned into an hour. An hour turned into two hours. Two hours turned into three hours.”

As the guards re-shackled the condemned man to lead him away, the prisoner started singing “I’m pressing on the upward way,” a hymn with the refrain, “Lord, plant my feet on higher ground.”

“I wanted to get condemned people on higher ground,” said Stevenson.

To do this work, Stevenson outlined five necessary things: having a strong sense of identity, being in proximity to those on the margins, creating different narratives and being willing to do uncomfortable things.

The lack of these five things things, according to Stevenson, leads to the justice system in its current form, where current predictions are that one in three black male babies and one in six Latino babies born now will go to prison.

“Our nation is having a little bit of an identity crisis,” said Stevenson.

To understand the crisis, Stevenson believes, we have to go back to history.

“I think we’re still compromised by our history of racial inequality,” he said. “We made up an ideology of white supremacy to legitimate enslavement, and we never dealt with it.”

Only by discussing old narratives and creating new ones, by creating an identity that does not accept bigotry and by becoming familiar with people who have been marginalized by those narratives, does Stevenson believe we can create a more just system.

Stevenson continues litigating cases — one of his juvenile clients was scheduled to be released after 27 years in prison during his Q&A session — but he is also expanding the work of EJI to include, among other things, a national lynching memorial in Alabama.

“I thought it was amazing,” said Scott Wagoner, pastor of Deep River Friends Meeting in High Point. “I was moved that he’s still doing the work, even though he’s on the speaking circuit.”

Stevenson ended his speech with an encouragement for people to engage in these discussions and to work toward more justice for people who are incarcerated.

“None of us want to be judged by our worst act,” he said. “I think of our work as your work.”