Kanye West and contrarian instincts

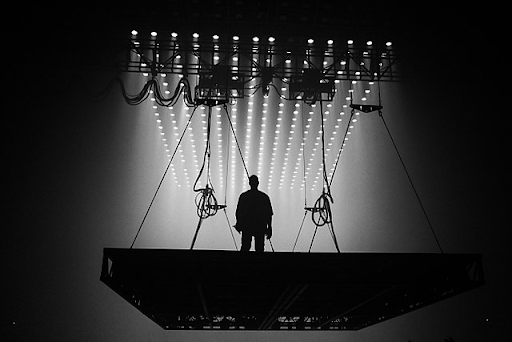

Ye in the TD Garden from the Saint Pablo Tour. One of the many apotheoses of old Kanye. Via Wikimedia Commons

Whenever I read new news about the downward spiral of Kanye West, I think back to the barbershop guy. This is not because they hold similar beliefs—the barber was just advocating for getting outside more, while Kanye has rapidly devolved into a unique brand of an antisemitic, pseudo-alt-right free-speech warrior. However, both of them, in their paths to their current beliefs, have acted on, and been influenced by, the same common impulses and conditions.

The first is the lack of a satisfactory framework. There exists no singular, satisfactory explanation for Black Americans from mainstream Black philosophy for why things are the way that they are.

The second and more intriguing is the power of contrarianism. Nothing galvanizes people to believe what they believe quite like people they don’t trust telling them they are wrong. My father is a prime example. He can be a strong contrarian who is incredibly hard to budge off of a point when he thinks he’s right. Failing to push him strengthens his resolve; every bit of energy put in to do so gets absorbed and used as fuel like a rhetorical suit of Vibranium.

In recent years, the reform efforts of those holding to the modern liberal framework, the one that preaches systemic change as the solution to our problems, have become less satisfying. The last vestiges of explicit legal racial discrimination have been eradicated, but problems persist. This isn’t surprising—life is complicated. However, that realization is not a fun one.

This dissatisfaction leads some Black people to adopt alternative grand narratives about why things are the way they are. Sometimes these frameworks are of the Dr. Umar, Dr. Sebi barbershop variety, which sees the Black disconnect from our cultural, spiritual and geographical heritage as an almost metaphysical cause for all of our problems.

Sometimes they are the harmful, Kanye West Black alt-right frameworks that blame some combination of Black people themselves, and oftentimes Jewish people, for the issues of modern Black America.

Both of these frameworks feed into a contrarian feedback loop. When the liberal-structuralist explanation doesn’t suffice, some Black people migrate over to one of the other frameworks. Some of these ideas breed distrust of their detractors from the offset, so when challenged, proponents can write off criticism and hold stronger to their beliefs.

This is self-defeating. While in some capacities, there may be some merit to appeals to individual responsibility for problems within the Black community, or attempts to connect with our cultural heritage, any framework that focuses solely on either of these will miss the still-existent structural issues.

The core issue, the main desire that feeds this self-deprecating cycle, is the yearning for a single, universal explanation, one set of principles and assumptions that explain why things are the way they are and how to fix them.

These do not exist. The world is too complex, and individual experiences are too unique for any framework to explain everything and offer a guide for how to proceed. There have been serious attempts; most modernist philosophy, I would argue, amounts to either attempts at creating frameworks or creating the procedures for deriving frameworks. But none quite hit the spot for the casual philosophical thinker, a.k.a everyone with free time.

The existence of these attempts is very attractive, and Black people, a people adrift without a framework, are particularly vulnerable to their temptations. But when we give in, we often fall into one of the two self-defacing feedback loops previously mentioned.

The solution here is to step back. There will not be a universal explanation for why things are the way they are in Black America, but we can explain bits. From bits, we can create our own patchwork framework, one that explains what it can explain but leaves some things unexplained.

While not as satisfying, a Black patchwork framework has two advantages over the attempts at grand frameworks. One, it would actually explain what it claims to be. Two, it would allow us to acknowledge that Black philosophy still has room to grow, and develop—that we aren’t simply benefactors of the ideas we hold true, rather, we are inheritors and, more importantly, contributors.

It’s good for us as people to attempt to find something that helps us make sense of the world, but we have to be careful not to let our desire pull us too far from where we start.