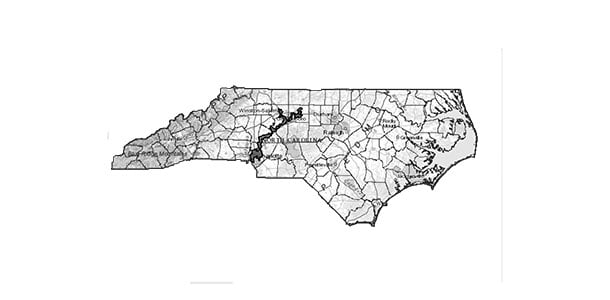

On a map, the 12th Congressional District of North Carolina takes a shape vaguely reminiscent of a dragon, snaking its way north along Interstate 85 from Charlotte to the Piedmont Triad. In the eastern portion of the state, the 1st District stretches in a nearly triangular figure, covering places from Henderson to New Bern and Elizabeth City.

The cartographers of these districts, the North Carolina General Assembly, crafted them back in 2011. On Feb. 5, the U.S. District Court for the Middle District of North Carolina ruled them invalid under the Fourteenth Amendment.

“Having found that the 2011 Congressional Redistricting Plan violates the Equal Protection Clause, the Court will require that new congressional districts be drawn forthwith to remedy the unconstitutional districts,” wrote Circuit Judge Roger L. Gregory in the case’s majority opinion.

With the North Carolina primary elections set to take place March 15, this recent court ruling potentially throws a wrench into voting plans. But, for many, this ruling is overdue.

“Gerrymandering and redistricting are probably the most unfair things in modern politics,” said Michael McShane, a sophomore political science major. “Instead of government by the people, it becomes government of the ruling class.”

According to senior Samantha Evans, creative district-drawing dates back to at least 1812, when Massachusetts Gov. Elbridge Gerry and state legislators rigged the state’s maps to favor Democratic-Republicans in the upcoming election. Gerrymandering today bears Gerry’s name.

“Districts are drawn by the party in power after the census is collected,” said Evans, a double major in political science and religious studies.

In the case of North Carolina, a Republican controlled legislature planned and approved the congressional districts that have been used since 2011. Leaders from that redistricting effort responded to the recent ruling Feb. 8.

“We trust the federal trial court was not aware an election was already underway and surely did not intend to throw our state into chaos by nullifying ballots that have already been sent out and votes that have already been cast,” said state Sen. Bob Rucho and state Rep. David Lewis in a joint statement. “We hope the court will realize the serious and far-reaching ramifications of its unprecedented, eleventh-hour action and immediately issue a stay.”

In the district court’s majority opinion, race played a large part in the drawing of the 1st and 12th Districts.

“(The Court was) recognizing with computers, though gerrymandering is an old practice, (that) we’ve achieved a whole new level,” said Professor of Economics Bob Williams. “There seems to be a practice of loading districts with voters of color.”

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, 53.5 percent of voters in the 1st District are black as well as 51.1 percent of voters in the 12th District. In the other 11 congressional districts of North Carolina, only one, the 4th District, had a black population totaling over 20 percent.

Drawing on his experiences growing up in Birmingham, Alabama, John K. Voehringer Jr. Professor of Economics Robert Williams sees echoes of the behavior that prompted the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

“This is something white people in power do to stay in power,” he said. “That’s what we lived with for more than a century after the Civil War.”

The districts, as they stand, do not infringe or restrict anyone’s right to vote. However, they do, as Robert Williams put it, channel voters into pools where their voices cannot be heard.

North Carolina is no stranger to legal battles over the ballot box.

In 1993, the 12th District was the subject of the Supreme Court case Shaw v. Reno, which altered how racially conscious redistricting efforts should be. In 2013, another Supreme Court case, Shelby County v. Holder, struck a provision from the Voting Rights Act that required states, including North Carolina, to have the federal government approve changes to voting laws.

The recent district court ruling is not related to a case involving the state’s controversial voter identification law, which the NAACP sued Gov. Pat McCrory over. The law, passed in 2013, took effect at the beginning of 2016.

“There’s almost no evidence of voter fraud that the ID law would offset,” said Bob Williams. “We should encourage people to take (voting rights) seriously and not put up barriers.”