Student talks “Zimbo Revolution”

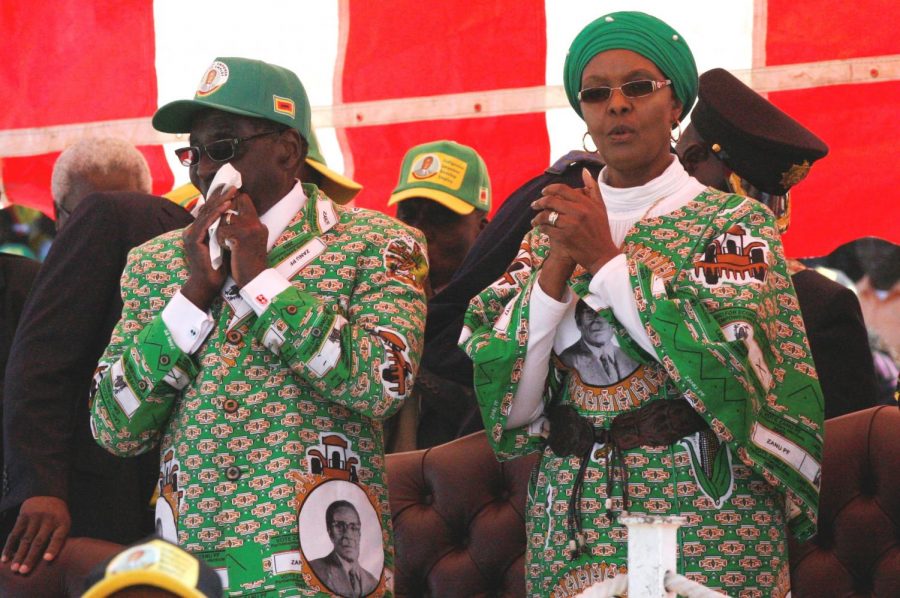

Grace Mugabe with Robert Mugabe.By User:DandjkRoberts – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=27559796

I knew change was in the air when my family’s WhatsApp chat started to blow up and wouldn’t cease for days.

What BBC and other western news outlets call a “coup”, much of the Zimbabwean people and military call a “necessary transition of power.” Either way, at approximately 5 a.m., on a seemingly ordinary Wednesday, the course of Zimbabwe’s history changed forever. On Nov. 15, the Zimbabwean military, equipped with tanks and soldiers, marched into the northern section of Harare, Zimbabwe. Within a few hours, the military general appeared on Zimbabwe’s national broadcasting stations and announced that President Robert Mugabe, his wife Grace Mugabe and many of the president’s close advisors were under house arrest. The story of what I like to call the “Zimbo Revolution,” however, had begun long before then with years of building tension and controversy.

Mugabe was widely revered when he first became prime minister in 1980, but bouts of hyperinflation, scandals and the like throughout his 37-year reign took a toll on both his reputation and public sentiment.

This, coupled with my country’s yearning to ease out of economic instability, led to a non-coup coup. If I could attribute this swift turn of events to one cause, I would point to Grace Mugabe’s interfaith rallies on Nov. 4 and 5. Grace Mugabe held these rallies to campaign for an official position in Zimbabwe’s government. The majority of her speeches were targeted towards Emmerson Mnangagwa, the Vice President of Zimbabwe. She challenged and was accusatory towards his policies, prompting many to believe she would be running for his office seat in the upcoming 2018 elections.

The encompassing problem arose two days later on Nov. 8 when Robert Mugabe fired Mnangagwa from his position with no constitutional impetus (note: this was when WhatsApp really began to heat up). Mnangagwa was then exiled and forced to flee the country. By then, several Zimbabweans speculated that Robert Mugabe may plan to appoint Grace Mugabe as his vice president, which would be nepotism at its best and unconstitutional at its worst. On Nov. 13, the military held a national conference call that focused on assessing the Mnangagwa crisis and how to approach the situation. This conference call was supposed to be broadcasted on the Zimbabwe Broadcasting Corporation network and ZimPapers, the country-run media platforms that reach all of Zimbabwe.

Within a couple of hours, their conference was blacked out by both platforms. Now the conspiracy theories were looming. Did Mugabe and Grace call the blackouts? What is the military discussing? On Nov. 15, we received our answer via the non-coup coup. To show a sense of solidarity, tens of thousands marched through Harare’s streets on Saturday, Nov. 17 to the statehouse in protest of Mugabe’s long-reigning rule. Millions marched, including Zimbabweans living outside of the US. Protests spanned as far as London and Cape Town. ZANU-PF, Mugabe’s political party, gave Mugabe until noon on Monday to resign as leader to make way for a new president.

The following few days were filled with restless nights, late-night calls, long presidential speeches and impeachment proceedings.

The threat of impeachment may have forced Robert Mugabe to take action, because on Nov. 21, he officially resigned. On Nov. 24, Emmerson Mnangagwa was sworn in as the new president.The group chat buzzed with happy emojis and huzzahs. My family ate at a restaurant to celebrate. I’m most proud of my country’s lack of violence through the whole endeavor. Although there was strain, there was no bloodshed.

After these restless weeks, we were finally able to sleep peacefully.