Vaccine prices may impede global recovery from the coronavirus

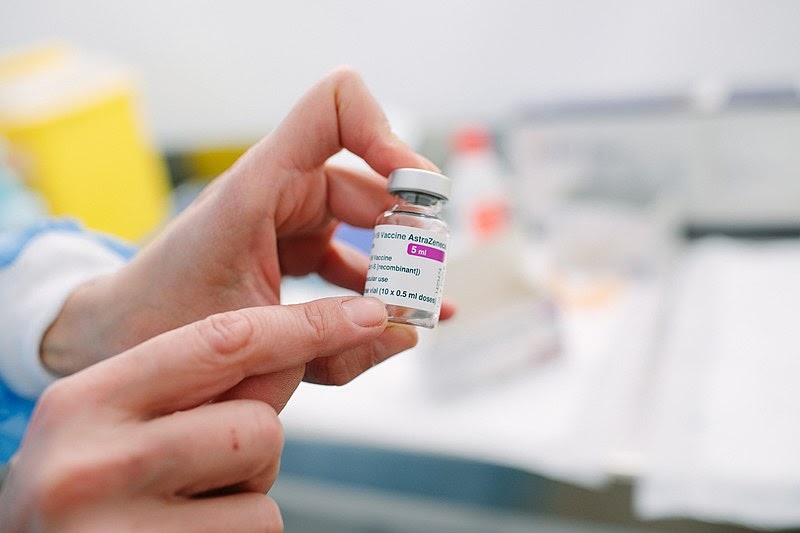

Oxford AstraZeneca COVID-19 Vaccine

Poorer countries may have little hope of sufficiently vaccinating populations, perhaps for years, as pharmaceutical giants’ vaccine distribution seems to be concentrated around several rich nations. However, the exclusion of less wealthy states from vaccine rollout has been an anticipated dilemma.

COVAX, an initiative started by the World Health Organization (WHO) and other international organizations, was created with the goal of creating a less severe divide between the vaccination capabilities of larger, wealthier countries and more vulnerable states. COVAX was initially to be funded by subsidies from several UN member states and by contributions from private foundations, money which would go to purchase vaccines mostly from AstraZeneca. The reality of this plan relies on the charitable spirit of countries like the U.S.

However, this initiative has faced backlash in response to a lack of transparency in AstraZeneca’s pricing. For example, this vaccine would cost Uganda almost three times as much as it would the European Union, according to data compiled by UNICEF. Specifically designed to be more inexpensive than its counterparts, AstraZeneca has not revealed how these inconsistent prices are determined. Rather than giving countries like Haiti the chance to even begin to vaccinate their populations, the program has instead promised millions of vaccines to Canada.

Orders like these may seem unjust. However, manufacturers of the vaccines could be the only entities capable of effectively regulating the prices of vaccines and determining which governments they go to.

“In an industry in which the drug companies set prices, it’s not a free market,” said Political Science Professor Ken Gilmore, “It’s an oligopoly; oligopolies are notorious for price fixing, even if they don’t do it explicitly.”

Pharmaceutical companies always charge different prices to various countries, but Gilmore suggested that the methods by which these prices are determined are especially flawed.

“They want to say it’s supply and demand, that it’s the number of vaccines you’re ordering. So, therefore, large population states should pay less—you get the quantity discount,” Gilmore explained regarding the process of price fixing by AstraZeneca and others. “But then weirdly enough, they say, it also has to do with your ability to pay. What they’re doing is saying, if you can afford to pay more, we’re going to charge you less.”

This custom aligns with the trend in data in which initially, wealthier and more supported countries end up paying less, and low income countries are left out of the rollout almost entirely at first.

“It’s the US healthcare system…” said Guilford junior and economics major Benjamin James. “We’ve ranked people based on how much they can pay and their track record.”

These two factors are fundamental to the prices that companies appear to be setting. Although it makes sense to charge prices proportionally to what a country may be able to afford, the actual results have been counterintuitive.

“This is price discrimination, and it will continue,” James said.“(The possibility that countries might donate or redistribute vaccines) only comes through fundraising and dual self interest.”

This idea that lower-income countries may not initially have independent access to the supply at all goes back to the role that pharmaceutical companies play in this structure of relief.

“The drug companies are making the decision of what the queue looks like,” said Gilmore. This indicates that although nations such as Uganda or Nepal may have a higher demand for the vaccine, countries like the U.S, Canada and European nations would still have priority.

The implications of this seem to shift the moral responsibility onto the prioritized countries, rather than the drug companies themselves. Because these countries are the first to have their orders recognized, they would have to become the administrators for equitable distribution.

This issue goes back to James’s point about mutual interest. Countries that were part of the rollout, particularly the United States, would have to donate portions of their vaccines and incorporate that into domestic scheduling for vaccinations. The issue of timing is particularly important in this case. If wealthy states don’t make any decisions to donate their doses, according to Dr. Gavin Yamey in a report by the Duke Global Health Institute, “the pandemic will drag on for perhaps as many as seven more years.” This predicament is likely, as few states can be expected to donate vaccines before a great portion of their populations are vaccinated.

“The world economy and globalization has made us all so interdependent that if Nepal doesn’t recover, we don’t fully recover,” James said.

Intertwined supply and manufacturing chains all further reinforce the need for a global plan for vaccine distribution. Thus, due outside pressure from health experts and advocates for small nations, and because of the inelasticity of pharmaceutical corporate price-determining practices, rich states may be responsible for coordinating—and funding— global vaccine supply.