Guilford community reacts to discovery of closest black hole to Earth

According to the Smihsonian, scientists estmate thar there are about 100 million black holes in our galaxy waiting to be discovered.

Astrology can be a popular topic on college campuses, while students are trying to figure out their place in the world and analyze others. Students are full of wonder, and college can be a crucial time to ask questions about the world and even the universe. On Nov. 4, astronomers found a black hole in Earth’s “backyard.”

According to the New York Times, Kareem El-Badry, an astrophysicist at The Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, discovered the closest known black hole, named Gaia BH1. The black hole is about 1,600 light-years away, and the next-closest known black hole is 3,000 light-years away, in the constellation Monoceros.

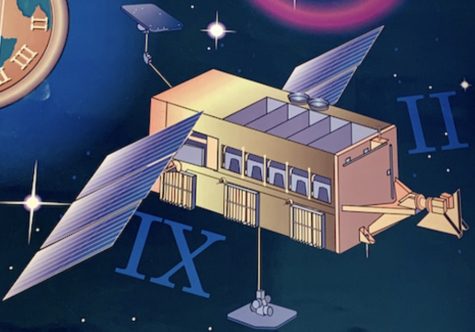

To find the black hole, El-Badry tracked data from the European spacecraft GAIA, which can track the motion and positions of stars in the Milky Way. According to the New York Times, “Dr. El-Badry and his team detected a star, virtually identical to our sun, that was jittering strangely, as if under the gravitational influence of an invisible companion.”

To see what this was, El-Badry and his team used the Gemini North telescope in Hawaii. They chose this telescope because it can measure the speed of an object and the movement around it. The data from the telescope showed that the object was not just a star, but a black hole.

Donald Smith, a physics professor at Guilford, discovered black holes during his time earning his Ph.D. at MIT using a satellite called the X-Ray Timing Explorer. Smith explained that a black hole is not a hole punched through something, but an object.

“…Think of it like a planet or a star crushed down to a very, very, very small size,” Smith said. “Earth would need to be crushed down to the size of a pea to be a black hole. The sun would be crushed down into something the size of a city…It gets that small but its gravity is so strong that not even light can get out of it, creating a black hole…The mass is the same. It’s just super, super concentrated.”

According to the Smithsonian, Gaia BH1 is about ten times bigger than our sun and is one out of 20 known black holes in the Milky Way. It is a dormant black hole, meaning that it does not emit high levels of X-ray radiation, making it even harder to discover. Scientists estimate that there are 100 million more black holes in our galaxy, bigger than Earth’s sun, waiting to be discovered. According to NASA, black holes result from a strong gravitational pull that doesn’t allow anything, even light, to escape. This is why scientists had to analyze motion to find Gaia BH1.

Parker O’Keefe, a first-year physics major at Guilford, explained her fascination with black holes: “I am interested in black holes because they can suck up matter and light itself. I love the mystery of where it goes or (whether) these elements are being destroyed, which brings other theories into question.”

O’Keefe hopes to study black holes in the future but wants to make sure that she fully understands the physics behind them.

“There’s a lot of complexity and knowledge required for getting to the bottom of it,” she said. She described her academic drive to learn more about physics, saying, “It is the science of everything around us: seen and unseen, and I find it fascinating.”

Eric Mortensen, a professor of religious studies at Guilford, a faculty advisor of the Cloud Gazing Society and a practicing Buddhist, offered his take on wonder and discoveries like Gaia BH1. Mortensen believes that science and religion work together, not against one another.

“That’s what religion is, a sense of trying to answer what we don’t know,” Mortensen said. He added that discovery and religion allow wonder: “It’s allowing curiosity. It’s allowing creativity and imagination.”

Mortensen has an idea of why humans wonder and continuously try to discover new things. “I don’t think we can help it,” he said. “I think we are always trying to look for meaning in things, whether or not we’re going to find them in, you know, things that are distant from our planet.”

According to Mortensen, through wonder and discovery, people can see how they fit into life and the universe around them. “One of the things that happen when you look through a telescope is that you begin to get a much more humble view of the world, that you do not see yourself as the center of things anymore,” Mortensen said.

Smith agrees with Mortensen: “…I would hope people would take away from this…that there’s so much out there still to be discovered, and it just takes time and the will to learn how to do it.”